Attacking the Heart of the German Industry

For a number of years now, a group of professional hackers has been busy spying on businesses all over the world: Winnti. Believed to be controlled by China. For the first time, in a joint investigation, German public broadcasters BR and NDR are shedding light on how the hackers operate and how widespread they are.

Unser Bericht zur digitalen „Söldnertruppe“, die Industriespionage betreibt.

Malware:

Malicious software, like computer viruses or Trojans.

This investigation starts with a code: daa0 c7cb f4f0 fbcf d6d1. If you know what to look for, you’ll find Winnti. Hackers who have been spying on businesses all over the world for years. A group, presumably China-based, has honed in on Germany and its DAX corporations. For the first time ever, BR and NDR reporters have successfully analyzed hundreds of the malware versions used for that unsavory purpose. The targets: At least six DAX corporations, the stock-listed top companies of the German industry.

Winnti is a highly complex structure that is difficult to penetrate. The term denotes both a sophisticated malware and an actual group of hackers. IT security experts like to call them digital mercenaries. Since at least 2011, these hackers have been using malware to spy on corporate networks. Their mode of operation: to collect information on the organizational charts of companies, on cooperating departments, on the IT systems of individual business units, and on trade secrets, obviously.

Asked about the group an IT security expert who has been analyzing the attacks for years replies, tongue in cheek: “Any DAX corporation that hasn’t been attacked by Winnti must have done something wrong.” A high-ranking German official says: “The numbers of cases are mind-boggling.” And claims that the group continues to be highly active—to this very day. The official’s name will remain undisclosed, as will names of the more than 30 people whom we were able to interview for this article: Company staff, IT security experts, government officials, and representatives of security authorities. They are either not willing or not allowed to speak frankly. But they are allowed to reveal some of their tactics.

This allows us to find the software and to figure out for ourselves how the attackers work. Thanks to the help received from the informers, we, the reporters, are able to get on to the group. Part of their trail is the following code: daa0 c7cb f4f0 fbcf d6d1.

Logging:

The hackers’ individual steps are stored in log files.

Modern-day espionage operations have one big advantage: Instead of painstakingly planting agents in companies, digital spies are simply sending prepared emails. Instead of taking pictures of confidential documents while the rest of the staff is out to lunch, hackers can remotely log on to company computers and send their commands from their keyboard. But every hacking operation also comes with a huge drawback. It leaves digital traces. If you notice hackers, you can log their every step. The hackers themselves have no clue that they are under meticulous scrutiny, sometimes even for months at a time.

To decipher the traces of hackers, you need to take a closer look at the program code of the malware itself. It can be found in databases operated by private companies like “Virustotal.” The company is owned by Google and is a kind of malware search engine. The information stored in that database is so valuable to IT consultants and security companies that they pay thousands of Euros per month for accessing it. Anybody who is unsure whether a mail attachment contains a Trojan can have it checked in that database by more than 50 antivirus programs. In return, Virustotal stores the file with the aid of a digital fingerprint. This digital fingerprint allows others to search for the file and to analyze the codes it contains. People like ourselves.

Every file has a digital fingerprint—which makes is clearly identifiable.

In former times, it was solely the job of intelligence agencies to uncover espionage operations. Nowadays, corporations and IT security companies prefer to employ staff earning six-figure salaries for that purpose. Their job is to search the corporate networks and Virustotal for evidence of hacker groups. After all, it is the companies they work for which are being spied on—and the companies’ secret formulas and building plans warrant absolute protection. Professionally, these employees are on a par with the security services. It is one of those professionals who meets with us and hands us a piece of paper.

“This might help you find the hackers”, the gentleman tells us. He believes that because they are spying on so many targets at the same time, they have to figure out how to keep track. He also believes that the hackers chose convenience over anonymity. We soon realize how incredibly negligent the hackers are. We are working with Moritz Contag, an IT security expert affiliated with Ruhr University Bochum (RUB). What we find: The hackers are writing the names of the companies they want to spy on directly into their malware. Contag has analyzed more than 250 variations of the Winnti malware and found them to contain the names of global corporations.

Opsec:

Operational Security. It is a collective term for all the steps taken by hackers to cover their tracks.

Hackers usually take precautions, which experts refer to as Opsec. The Winnti group’s Opsec was dismal to say the least. Somebody who has been keeping an eye on Chinese hackers on behalf of a European intelligence service believes that they didn’t really care: “These hackers don’t care if they’re found out or not. They care only about achieving their goals."

The sheet of paper the staff member is showing us has a code printed on it: daa0 c7cb f4f0 fbcf d6d1. We are looking for the same string of characters in Virustotal, the gigantic database of infected files. And we succeed.

Step 1: At the end of a Windows file we find the following code: daa0 c7cb f4f0 fbcf d6d1. This is the data stream in which Winnti hackers are hiding their commands.

Step 2: It is a piece of cake to unmask the data. From this point, it is easy to see what the hackers are up to. daa0 c7cb f4f0 fbcf d6d1 transforms into C:\Windows, a file path on the Microsoft operating system.

Step 3: For the hackers to keep track of which network they are currently invading, they simply write it directly into their program. In the example shown herein, the Winnti hackers are inside the networks of Gameforge.

Phase 1: Cybercrime

It would seem that during the early stages, the hackers were concerned mainly about making money. Gameforge is a case in point: a gaming company based in the German town of Karlsruhe. During its heyday, the company had a staff of 700 working hard at conquering the global gaming market, and boasted annual sales to the tune of 140 million Euros. Gameforge offers so-called “freemium” games. While playing the games is free, those who want more either have to earn virtual money by completing certain tasks, which takes a long time, or shell out real money.

We are told that in 2011, an email message found its way into Gameforge’s mailbox in Karlsruhe. A staff member opened the attached file and unbeknownst to him started the hackers’ Winnti program. Shortly afterwards, a few players became virtual rich persons.

The administrators became aware that someone was directly accessing Gameforge’s databases and raising the account balance. They started getting worried. How could this be happening? The technicians used the next maintenance interval to reinstall the servers of the affected game. The players didn’t have a clue about what’s going on. No sooner were the servers back up than the manipulations continued.

Gameforge was using Kaspersky antivirus software, which didn't cause any alarm bells to ring. Gameforge arranged for Kaspersky's IT security experts to come directly to Karlsruhe. Because obviously there was something weird going on. Nobody informed the State Bureau of Criminal Investigation or the local police. The year was 2011, and many investigators were barely familiar with the term or concept of cybercrime.

While keeping an eye on Gameforge’s corporate network, the IT security experts did find suspicious files and decided to analyze them. They noticed that the system had in fact been infiltrated by hackers—who were acting like Gameforge’s administrators most of the time. Which allowed them to remain invisible. It turned out that the hackers have taken over a total of 40 servers.

Persistent:

It is very hard to permanently remove the hackers from the network.

This mode of operation is typical of many hacker groups—and especially of Winnti. “They are a very, very persistent group,” says Costin Raiu, who has been watching Winnti since 2011. Raiu is in charge of Kaspersky’s malware analysis team. “Once the Winnti hackers are inside a network, they take their sweet time to really get a feel for the infrastructure,” he says.

The hackers will map a company’s network and look for strategically favorable locations for placing their malware. They keep tabs on which programs are used in a company and then exchange a file in one of these programs. The modified file looks like the original, but was secretly supplemented by a few extra lines of code. From now on, this manipulated file does the attackers’ bidding.

Winnti is very specific to Germany. It is the attacker group that's being encountered most frequently.

Raiu and his team have followed the digital tracks left behind by some of the Winnti hackers. “Nine years ago, things were much more clear-cut. There was a single team, which developed and used Winnti. It now looks like there is at least a second group that also uses Winnti.” This view is shared by many IT security companies. And it is this second group which is getting the German security authorities so worried. One government official puts it very matter-of-factly: “Winnti is very specific to Germany. It is the attacker group that's being encountered most frequently."

Phase 2: Industrial espionage

By 2014, the Winnti malware code was no longer limited to game manufacturers. The second group’s job is mainly industrial espionage. Hackers are targeting high-tech companies as well as chemical and pharmaceutical companies. We find evidence going as far as mid-2019. Cases of espionage which were probably still ongoing when we discovered them. Winnti is attacking companies in Japan, France, the U.S. and Germany. Or more precisely: in Düsseldorf.

Most people probably know the DAX company Henkel as a manufacturer of detergents and shampoos. But Henkel offers a huge range of other products, including adhesives for industrial applications. Modern cars are glued instead of welded. In a commercial on Youtube, Henkel shows staff members successfully joining two metal plates with just three grams of adhesive and then using the plates to pull a 280-ton train. Nearly half of Henkel’s annual sales of 20 billion Euros are generated by Henkel’s so-called “adhesive technologies".

The Winnti hackers broke into Henkel’s network in 2014. We have three files showing that this happened. Each of these files contains the same website belonging to Henkel and the name of the hacked server. For example, one starts with the letter sequence DEDUSSV. We realize that server names can be arbitrary, but it is highly probable that DE stands for Germany and DUS for Düsseldorf, where the company headquarters are located. The hackers were able to monitor all activities running on the web server. And they also seemed to be able to reach systems which didn't have direct internet access: Internal storage files and possibly even the intranet.

The corporation confirms the Winnti incident and issues the following statement: “The cyberattack was discovered in the summer of 2014 and Henkel promptly took all necessary precautions.” Henkel claims that a “very small portion” of its worldwide IT systems had been affected— the systems in Germany. According to Henkel, there was no evidence suggesting that any sensitive data had been diverted.

How we worked

BR and NDR reporters, in collaboration with several IT security experts, have analyzed the Winnti malware. It was notably Moritz Contag of Ruhr University Bochum who managed to extract information from different varieties of the malware. Contag wrote a script for this analysis. You can find it here. Silas Cutler, an IT security expert with US-based Chronicle Security, has confirmed Contag’s analyses.

Far from attacking Henkel and the other companies arbitrarily, Winnti takes a highly strategic approach. Which is perfectly evident from the other cases. Take Covestro, for example, also a manufacturer of adhesives, lacquers and paints. This chemical corporation, a Bayer spin-off, is now listed on the DAX. Covestro is regarded as Germany’s most successful spin-off in the recent past. Up until June 2019, they had at least two systems on which the Winnti malware had been installed. Although there is no concrete evidence of data loss, Covestro considers “this evidence of infection to be a serious attack on our company.” Another manufacturer of adhesives, Bostik of France, was infected with Winnti in early 2019.

The hackers behind Winnti have also set their sights on Japan’s biggest chemical company, Shin-Etsu Chemical. We have in our hands several varieties of the 2015 malware which was most likely used for the attack. In the case of another Japanese company, Sumitomo Electric, Winnti apparently penetrated their networks during the summer of 2016. And consider Roche, one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world: the sheer number of files, 25 in total, gives you an idea of the degree of network penetration by the hackers. Winnti hackers also penetrated the BASF and Siemens networks. Both corporations have confirmed our research data.

A BASF spokeswoman tells us in an email that in July 2015, hackers had successfully overcome “the first levels” of defense. “When our experts discovered that the attacker was attempting to get around the next level of defense, the attacker was removed promptly and in a coordinated manner from BASF’s network.” She added that no business relevant information had been lost at any time. According to Siemens, they were penetrated by the hackers in June 2016. “We quickly discovered and thwarted the attack,” Siemens told us in a written reply. Siemens claims that even after detailed analyses, no evidence suggesting data loss from the attack has been found to date.

Targeted companies

- Gaming: Gameforge, Valve

- Software: Teamviewer

- Technology: Siemens, Sumitomo, Thyssenkrupp

- Pharma: Bayer, Roche

- Chemical: BASF, Covestro, Shin-Etsu

Bostik, Sumitomo and Shin-Etsu didn’t respond to our requests for comments at all. Roche chose to keep their response neutral. A spokesperson replied that “information security and data protection are taken very seriously.” Nearly all major corporations now emphasize that there is no such thing as one hundred percent protection. Hacking attacks on large companies have become almost commonplace. And yet: No company really likes to talk about having hackers in its own networks. In many cases, customers are not informed. They are justifiably scared of damage to their reputation.

Teamviewer is a case in point. A company based in the southwest of Germany, a bona fide Silicon Valley contender, and a true showpiece enterprise. It was quickly traded at a nine-digit valuation, the highest accolade for a newly incorporated enterprise. Then came the Winnti hackers. “Spiegel” magazine was the first to report about it.

The corporation offers a remote maintenance software solution which, according to Teamviewer, is installed on two billion devices. To imagine the mayhem a hacker might cause by infiltrating the end users’ devices via the Teamviewer application—it boggles the mind. But things didn’t get that far for Teamviewer, the company assures us. They add that they replaced their entire IT infrastructure and spent millions on removing the hackers from their networks in 2016.

The second way to find Winnti

For the IT departments, the infected computers are extremely difficult to detect. That is because a new variety of this malware remains perfectly passive as long as it is left alone. How can you find something that’s playing dead? Since 2018 there’s a public tool available designed to systematically trawl the Internet for these infected systems. This network scan works by luring the software out of its hiding spot.

Each company has its own IP address range. The IP address is a computer’s unique address. This is how computers can be reached via the Internet.

Once the Winnti malware has infected a computer, it initially behaves passively. Winnti is now waiting for control commands.

With the aid of special software we send requests to different company networks. The software per se is harmless, but capable of simulating control commands designed to lure Winnti out of hiding.

In all cases where Winnti was installed, the malware will respond to our request. This tells us: That company has been hacked.

Have you kept count?

So far, ten companies have been affected, most of them in Germany.

This tool hit pay dirt at Covestro and Bostik. Many IT companies are taking the same route to find Winnti infected computers; some of the results have been leaked to us—in the strictest confidence. Thanks to this tool, we found out back in March 2019 that the Bayer pharmaceutical group had been hacked by Winnti.

The tool was written by staff of Thyssenkrupp, because the industrial giant—company number eleven—had been spied on by Winnti. In 2016, the corporation allowed a reporter from “Wirtschaftswoche” to watch the attackers being pushed back. The magazine later wrote of a “six-month defensive battle.” The hackers had succeeded in extracting small data sets of importance for the construction of plants. The company mentions “data fragments” and believes that the hackers have missed their actual target, tapping into the corporation’s research results.

The trail leading to China

At Gameforge, the Winnti hackers had already been removed from the networks when a staff member noticed a Windows start screen with Chinese characters. Presumably, the hackers were using tools in their native language, which would have made their work easier. But they forgot to cover up their tracks. Just another mistake they made, one of many.

In October 2016, several DAX corporations, including BASF and Bayer, founded the German Cyber Security Organization (DCSO). The job of DCSO’s IT security experts is to observe and recognize hacker groups like Winnti and to get to the bottom of their motives. In Winnti’s case, DCSO speaks of a “mercenary force” which is said to be closely linked with the Chinese government. They have been tracking the group for a long time: “We can, based on many, many indicators, say with high confidence that Winnti is being directed by the Chinese.”

We can, based on many, many indicators, say with high confidence that Winnti is being directed by the Chinese

Many of the experts we talked to believe that the group is operating out of mainland China. “I don’t care if the hackers work in green uniforms or are commissioned by people wearing green uniforms,” says an IT security expert, alluding to a suspected proximity to the country’s military intelligence service.

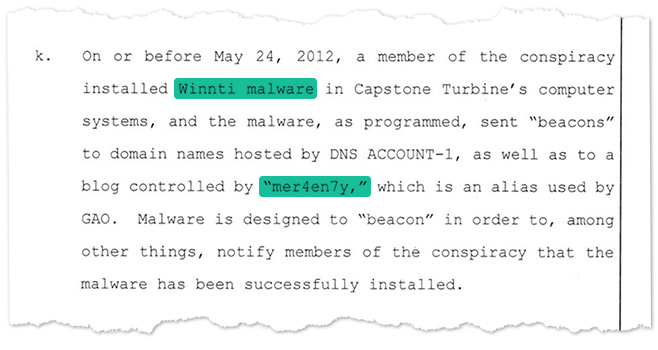

It would seem that in the early days, Winnti hackers were still quite careless. One of them left many traces on the Internet. In 2013, the Kaspersky team was able to follow clues in their code. This is how Costin Raiu and his colleagues came across a person using the alias “Mer4en7y.” This individual was active in hacker forums where he commented in Chinese on a job offer for recruiting hackers. There was mention of a “powerful background.” “And ‘Mer4en7y’ replied that the job was too far away for him, but that he was in full support of the work,” says Raiu.

On 30 October 2018, the US government brought charges against ten Chinese nationals. Two of them are believed to be working for one of China’s intelligence services. Hackers are charged with spying on a manufacturer of gas turbines. Also charged in connection with the crime: “Mer4en7y”, who is believed to have been acting on behalf of the intelligence service and to have used the Winnti software for the hack. IT security experts attribute the cyberattack to a different Chinese group. But the charges filed are testimony to the close links between at least one Winnti hacker and the government.

The US government is accusing the individual going by the alias Mer4en7y of using the Winnti software

Janka Oertel of the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) in Berlin has been keeping a close eye on China. Oertel considers it “very unlikely that large-scale cyber operations could be happening without at least parts of the Chinese party-state knowing about them.” Oertel, a political scientist, emphasizes that China wants to play a “significant market role” in key industries such as materials research by 2025 and to dominate the world market by 2035. “In some of these areas, however, China has not yet managed to achieve its goals without technology transfers—including transfers from Germany,” Oertel adds.

A government official familiar with the hacking cases agrees: “Cyber incidents allow us to draw conclusions as to a nation’s true priorities.” The point, he believes, is to understand one’s own industry and to figure out what cannot be produced fast enough. The missing materials are then procured by hacking operations.

But a former staffer of a European intelligence agency warns: “If I wanted to hack anyone right now, I’d make it look like a Chinese group.” He warns against underestimating the proficiency of hackers working for governments. After all, he says, laying false trails is their job.

People working for the German intelligence agencies tell us that, although all current findings suggest that Winnti originates from China, much of the evidence is based on data that is several years old. “We have a knowledge gap for the past two to three years,” says one individual familiar with the incidents.”

If I wanted to hack anyone right now, I’d make it look exactly like a Chinese group.

While Germany does address industrial espionage in direct talks with the Chinese leadership, these attempts are considered a waste of time. “Fruitless,” says one individual who knows how these meetings work. The other side denies everything, he says, and what’s left at the end of the day are meaningless declarations of intent. And the Germans are hesitant to provide concrete evidence—for fear of revealing to the Chinese leadership what they know— for example, from the work of the Federal Intelligence Service (BND).

The BND is trawling the internet for specific groups of attackers. The agency received 300 million Euros to set up a powerful surveillance system, among other things. The idea is to find hacker groups suspected of being government backed and likely to cause damage to the Federal Republic. There is also talk of starting an “intelligence offensive” against Chinese groups of attackers. This means: Hacking into the networks. Spies watching spies.

Political espionage?

Corporations like Bayer, Covestro, Roche and Bostik share a single common denominator: the chemical sector. However, analyses also show that a number of targets now affected are deviating from the known pattern. We are talking about the possibility of political espionage. We have come across several indicators corroborating this suspicion.

The Hong Kong government was spied on by the Winnti hackers. We found four infected systems thanks to the network scan, and proceeded to inform the government by email. They confirm our findings: “Recently, it was found that six Internet facing computers of two government departments returned positive results from a test for Winnti malware.” The affected computers did not contain any classified information or citizens’ personal data, and there was “no evidence” that any data have been copied out, we are being told.

The network scan also sniffs out a telecommunications provider from India, which happens to be located precisely in the region where the Tibetan government in exile (the “Central Tibetan Administration”) has its headquarters. Incidentally, the relevant identifier in the malware is called “CTA.” A file which ended up on Virustotal in 2018 contained a pretty straightforward keyword: “tibet”. The CTA didn’t respond to our requests for comment.

Podcast (in German): How we deciphered the code

On top of this there are campaigns which don’t seem to make a lot of sense unless you consider political espionage. Take Marriott, the hotel chain based in Maryland, USA. The corporation manages more than one million rooms worldwide. While Marriott hotels may be state-of-the-art, who would want to hack Marriott for cutting-edge technologies or innovative ideas? Who would want to spy on the Indonesian airline Lion Air for the same reasons? Probably nobody. But hotels and airlines collect data. If you know how to access these data, you know where people travel and where they spend the night. And if you also hack into telecommunications companies you know where these people are located at any given time. The Winnti hackers managed to penetrate the networks of Lion Air and several telecommunications companies, and they at least did take Marriott into their sights. We have the relevant coded file in our hands.

When reached for comment, the German government tells us that the security authorities have established “multiple platforms and discussion groups” for that matter. If required, affected companies can request “appropriate advice and assistance for cleaning up their systems and further prevention.” In July 2019 the Federal Office for Information Security reached out to a company, whose name was included in a Winnti implant. We were told that “generally speaking foreign intelligence agencies have established cyberattacks as a vital mode of acquiring more information.” According to the government, these hackers usually don’t have to fear political or economical risks, “due to various obfuscation methods."

The German government’s response is elusive, when asked whether there is a connection between the Winnti hackers and the Chinese Government. They tell us that cyberattacks are taken seriously, no matter who is responsible. We reached out to the Foreign Ministry of China and the embassy in Berlin with this and other questions. We didn't hear back.